What is touch and how do we feel touch? Why is touch important and what is its importance?

Introduction

Touch is one of the five main senses that humans have, along with sight, hearing, smell, and taste. It is an essential aspect of our interaction with the world around us, allowing us to perceive pressure, temperature, and pain. The sense of touch is mediated by the complex nervous system, which sends signals from the skin and other touch receptors to the brain, where they are interpreted as different sensations.

The skin, the body’s largest organ, plays a crucial role in the sense of touch. It is home to a variety of nerve endings and receptors that respond to different stimuli. These include mechanoreceptors for pressure and vibration, thermo receptors for temperature changes, and nociceptors for pain.

Touch is not only vital for physical interaction with our environment—helping us to avoid harm, manipulate objects, and navigate our surroundings—but also plays a significant role in emotional and social interactions. Physical contact, such as hugging, holding hands, or a pat on the back, can convey comfort, love, and a sense of belonging. It has been shown to have numerous psychological and physiological benefits, including reducing stress, improving mood, and strengthening interpersonal connections.

The science of touch, or haptics, encompasses the study of touch sensation and its effects. It also includes the development of technology to replicate or enhance touch sensations in various applications, such as virtual reality, robotics, and medical devices, aiming to deepen our understanding and utilization of this fundamental sense.

Different types of touches

Touch, being a multifaceted sense, can be categorized in several ways based on the type of sensation experienced or the emotional context of the touch. Here’s an overview of different types of touch based on these perspectives:

Based on Sensation

Touch depends on our acceptance. How we want to accept touch. There are many types of touch. The first is visual touch. The experience we get through physical touch, touch gives a unique experience according to which a person can assess his perception or behavior towards the other person. The whole psychology of touch depends on the purpose for which the toucher is touching. That’s why touch is important.

Actually there are many types of touch but we will talk about only a few types of touch such as there are three different types of touch.

1. Mechanical Touch:

This involves sensations related to pressure, vibration, and texture. Mechanoreceptors in the skin detect these stimuli, allowing us to feel the weight of an object, the roughness of a surface, or the vibration of a phone.

Mechanical touch, one of the primary types of tactile sensations, involves the perception of physical forces such as pressure, vibration, and texture. This form of touch is crucial for interacting with our environment, enabling us to feel the shape, weight, and surface properties of objects, as well as the force of impact or contact with them. The detection and interpretation of mechanical touch are mediated by specialized sensory receptors in the skin known as mechanoreceptors. Here’s a closer look at how mechanical touch works and the types of mechanoreceptors involved:

Mechanoreceptors

Mechanoreceptors are nerve endings or specialized cells capable of converting mechanical stimuli into electrical signals that the nervous system can understand. Different mechanoreceptors respond to various aspects of mechanical touch:

Merkel Discs (Merkel cell neurite complexes): These receptors are sensitive to light touch and pressure, providing detailed information about the texture and shape of objects. They are especially concentrated in areas requiring high tactile acuity, such as the fingertips and lips.

Meissner’s Corpuscles: Located just below the skin’s surface, primarily in sensitive and hairless areas (like the fingertips, palms, and soles of the feet), these receptors respond to light touch and changes in texture. They are particularly attuned to detecting low frequency vibrations and play a significant role in grip control.

Pacinian Corpuscles: These are deep in the skin and also in other tissues such as the fascia and joint capsules. They respond to deep pressure and high frequency vibration. Pacinian corpuscles are adept at detecting rapid vibrations and pressure changes, contributing to our ability to feel engine vibrations or the sensation of a cell phone buzzing.

Ruffini Endings: Sensitive to skin stretch and sustained pressure, these receptors help monitor the slippage of objects across the skin and contribute to our sense of finger position and motion. They provide information about the direction of forces and the shape of objects.

Processing of Mechanical Touch

When a mechanical stimulus activates a mechanoreceptor, it triggers the receptor to generate an electrical signal. This signal is then transmitted along sensory neurons to the spinal cord and up to the brain, particularly the somatosensory cortex, which processes and interprets the signal as a specific touch sensation, like the texture of a fabric or the grip of a handshake.

The sensitivity and distribution of these mechanoreceptors vary across the body, accounting for differences in tactile acuity. For example, the fingertips are highly sensitive to fine details due to a high concentration of Merkel discs and Meissner’s corpuscles, while the back or legs, which have fewer of these receptors, are less sensitive to fine tactile details.

Understanding mechanical touch and its underlying mechanisms not only provides insights into human sensory perception but also informs the development of technologies that replicate touch sensations, such as haptic feedback in virtual reality systems and robotic devices.

2. Thermal Touch:

Mediated by thermo receptors, this type of touch allows us to perceive temperature changes. We can sense warmth, coolness, or the more extreme sensations of heat and cold.

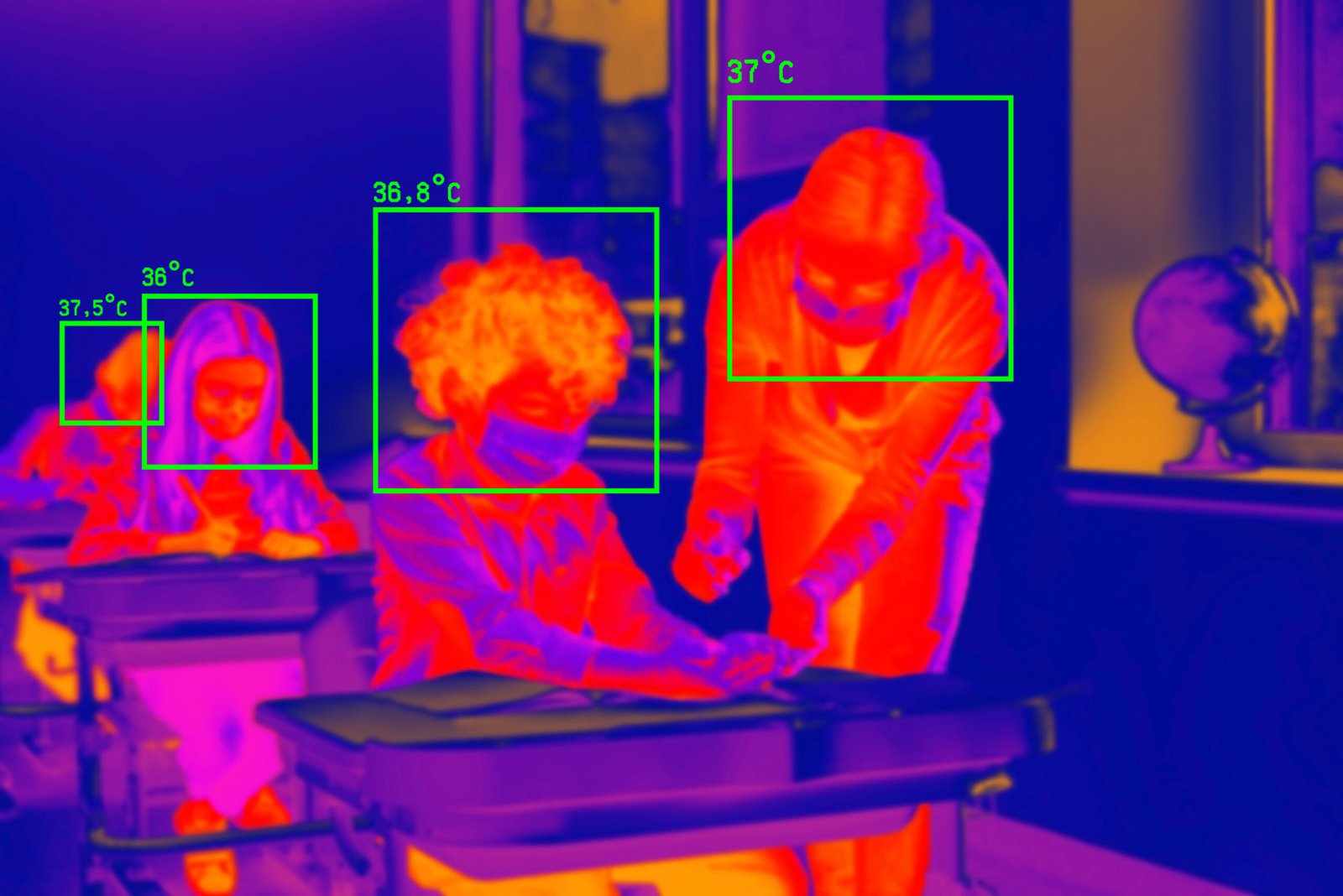

Thermal touch refers to the ability to sense temperature changes through the skin, enabling us to perceive warmth and cold. This sensory capability plays a crucial role in protecting us from environmental hazards, such as extreme heat or cold, and contributes to our overall sensory experience of the world around us. The sensation of thermal touch is mediated by thermo receptors, specialized sensory nerve endings that respond to variations in temperature.

Types of Thermo receptors

There are two primary types of thermo receptors, each sensitive to different temperature ranges:

Warm Receptors: These receptors are activated by temperatures above skin temperature (about 30°C to 36°C or 86°F to 97°F), but they start to respond more vigorously as temperatures rise, up to a threshold where heat becomes painful (around 45°C or 113°F). Beyond this threshold, the sensation of heat is no longer processed by warm receptors but by nociceptors that perceive pain.

Cold Receptors: These receptors are activated by a decrease in temperature below the normal skin temperature. They are most responsive to temperatures between approximately 20°C to 35°C (68°F to 95°F). Below a certain point, typically around 10°C (50°F) or colder, cold sensation also transitions to pain, again mediated by nociceptors.

Mechanism of Action

Thermo receptors transduce thermal energy into electrical signals through a process that involves transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. These channels are ion channels that open or close in response to changes in temperature, allowing ions to flow across the receptor’s membrane, thereby generating an electrical signal. This signal is then transmitted through sensory neurons to the spinal cord and onto the brain, where it is processed and perceived as warmth or cold.

Integration with Other Sensory Modalities

The perception of temperature is often integrated with other sensory modalities, such as touch and pain, to form a comprehensive sensory experience. For example, touching a cold piece of metal can feel different from touching a piece of ice, even if both are at the same temperature, due to differences in thermal conductivity and the presence of moisture. Similarly, extreme temperatures that activate nociceptors can produce a painful burning or freezing sensation, illustrating the overlap between thermal sensation and pain perception.

Adaptive Functions

The ability to sense temperature is essential for survival, as it helps organisms regulate their body temperature (thermoregulation) and avoid environmental hazards. Thermal touch contributes to behaviors such as seeking warmth when cold, removing a hand from a hot object to prevent burns, or finding an environment with an optimal temperature for comfort and safety.

Understanding the mechanisms behind thermal touch has implications beyond basic science, influencing fields such as medicine, where it can help diagnose and treat sensory disorders, and technology, where it inspires the development of devices that can simulate temperature sensations for virtual reality and prosthetic applications.

3. Painful Touch:

Nociceptors are responsible for detecting potentially harmful stimuli, resulting in the sensation of pain. This can be a sharp, immediate pain to alert us of injury, or a dull, chronic pain signaling ongoing issues.

Painful touch, or nociception, is the sensory process that alerts us to damage or potential damage to our tissues, serving as a critical protective mechanism. Unlike other types of touch that help us identify the properties of objects or environmental features, painful touch is primarily a warning system. It signals through distinct pathways to inform the brain about harmful stimuli, prompting reactions that aim to minimize injury and facilitate healing.

Types of Pain

Pain can be categorized based on various factors, including its duration, source, and specific qualities:

Acute Pain: This type of pain is sudden and typically sharp in quality, serving as an immediate reaction to a potential or actual injury. It usually lasts for a short period and resolves as the underlying cause heals.

Chronic Pain: Unlike acute pain, chronic pain persists for long periods, often without a clear cause. It can continue even after the initial injury has healed, becoming a health condition in its own right.

Somatic Pain: Originating from the skin, muscles, bones, or connective tissues, somatic pain is often well localized, meaning individuals can typically pinpoint its exact location.

Visceral Pain: This type of pain comes from the internal organs and the linings of cavities in the body. It’s often described as pressure or a deep squeezing sensation and can be more difficult to localize than somatic pain.

Mechanisms of Nociception

Nociception involves the detection of noxious (harmful) stimuli by nociceptors, which are specialized sensory receptors. These receptors can respond to various types of damaging stimuli:

Thermal Nociceptors: React to extreme heat or cold that can cause tissue damage.

Mechanical Nociceptors: Activated by intense pressure or mechanical deformation (such as cutting or crushing) that could injure tissues.

Chemical Nociceptors: Sensitive to chemical substances released by damaged tissue or inflammatory processes, such as bradykinin, histamine, and prostaglandins.

When activated by noxious stimuli, nociceptors generate electrical signals that travel through sensory neurons to the spinal cord and then to the brain. This pathway allows the brain to process and interpret these signals as pain, locate the source of the pain, and assess its intensity and quality.

Pain Modulation

The perception of pain is not merely a direct result of nociceptive signaling; it can be modulated by various factors at different levels of the nervous system. Psychological factors such as attention, emotional state, and prior experiences can significantly influence pain perception. Moreover, the body has mechanisms to suppress or amplify pain signals, such as the release of endogenous opioids (natural pain relieving substances) and the activation of descending inhibitory pathways that can dampen pain signaling.

The Role of Pain

While often unpleasant, pain is essential for survival. It encourages behaviors that protect injured or vulnerable parts of the body, such as resting an injured limb to promote healing. Pain also motivates avoidance of potentially harmful situations in the future, serving an important educational role.

Understanding the mechanisms of painful touch and its modulation is crucial for developing effective pain management strategies, including pharmacological treatments, psychological approaches, and physical therapies. Despite its protective role, when pain becomes chronic or is inadequately managed, it can significantly impair quality of life, highlighting the importance of ongoing research and innovation in pain science.

4. Proprioceptive Feedback:

While not touch in the traditional sense, proprioception involves the sense of the position and movement of our body parts. It’s closely linked to touch as it requires interaction with our environment and informs our sense of spatial awareness and coordination.

Proprioceptive feedback, often referred to simply as proprioception, is a crucial sensory system that informs us about the position and movement of our bodies in space. Sometimes dubbed the “sixth sense,” proprioception enables us to know where our limbs are and how they’re moving without having to look at them. This feedback system is essential for coordinating movement, maintaining balance and posture, and performing complex tasks that require precise timing and spatial awareness.

Mechanisms of Proprioception

Proprioception relies on specialized sensory receptors located in our muscles, tendons, joints, and inner ear. These receptors monitor the degree of stretch, tension, pressure, and movement within our body parts and provide continuous feedback to the brain about our body’s position and motion. The primary components include:

Muscle Spindles: Embedded in skeletal muscles, muscle spindles detect changes in muscle length (i.e., how much a muscle is stretched) and the rate of that change. They play a key role in regulating muscle contraction and coordinating fine motor control.

Golgi Tendon Organs: Located at the junctions between muscles and tendons, these receptors sense changes in muscle tension. They help prevent muscle damage from excessive force by triggering relaxation of overly contracted muscles.

Joint Kinesthetic Receptors: Found in the synovial joints, these receptors detect the degree of joint movement and pressure, contributing to the awareness of joint position and movement.

The Role of the Central Nervous System

Information from proprioceptive receptors travels via sensory neurons to the spinal cord and then to the brain, particularly to areas such as the cerebellum, the somatosensory cortex, and other parts of the central nervous system involved in motor control and spatial awareness. This integrated processing allows the brain to create a comprehensive internal map of the body’s position and movements, facilitating smooth and coordinated physical actions.

Importance of Proprioceptive Feedback

Proprioceptive feedback is fundamental to virtually all voluntary movements and many automatic responses:

Movement Coordination: It enables the coordination of limbs and body parts for complex movements like walking, running, jumping, and throwing.

Balance and Posture: Proprioceptive information is critical for maintaining balance and an upright posture, adjusting muscle activity to counterbalance the pull of gravity and other external forces.

Skill Learning and Performance: It allows for the refinement of motor skills through practice, as the body learns to anticipate and correct for variations in movement to achieve desired outcomes.

Injury Prevention: By providing realtime feedback on the limits of movement and stress on muscles and joints, proprioception helps prevent overextension and injury.

Proprioception and Rehabilitation

In cases of injury or neurological conditions, proprioceptive sense may be impaired, affecting movement and coordination. Rehabilitation exercises often aim to improve proprioceptive awareness, helping individuals regain control and precision of their movements. Techniques may include balance training, targeted exercises to enhance muscle coordination, and activities that challenge the body’s spatial orientation to retrain the brain and nervous system in processing and responding to proprioceptive signals.

Understanding and enhancing proprioceptive feedback is a key aspect of physical therapy, sports training, and rehabilitation, underscoring its fundamental role in human movement and physical health.

The explanation of Different types of touches

Based on Emotional Context

1. Affectionate Touch:

This includes gentle, loving touches such as hugs, kisses, and caresses. Affectionate touch is crucial for forming emotional bonds between humans, conveying love, comfort, and reassurance.

Affectionate touch, a fundamental aspect of human connection and communication, encompasses a range of physical interactions that convey warmth, care, love, and emotional support. This type of touch is integral to human bonding and has significant psychological and physiological benefits, underscoring its importance in human development and relationships. Affectionate touch includes behaviors such as hugging, cuddling, holding hands, gentle stroking, and patting, and is central to familial, platonic, and romantic bonds.

Psychological and Physiological Effects

Affectionate touch has profound effects on both mental and physical wellbeing, influenced by the release of certain neurotransmitters and hormones. Key benefits include:

Reduction of Stress and Anxiety: Physical touch can lower cortisol levels, a hormone associated with stress, thereby reducing feelings of anxiety and promoting a sense of calm.

Enhancement of Bonding: Touch stimulates the release of oxytocin, often referred to as the “love hormone” or “bonding hormone.” Oxytocin enhances feelings of trust, empathy, and connection, reinforcing social bonds and relationships.

Improvement in Mood: The action of touching and being touched can increase levels of serotonin and dopamine, neurotransmitters that play key roles in mood regulation. This can help alleviate symptoms of depression and enhance overall mood.

Boost to Immune System: Some research suggests that affectionate touch can have a positive effect on the immune system, potentially reducing the likelihood of disease by decreasing stressrelated physiological responses.

Pain Reduction: The analgesic effects of touch, partly mediated by the release of endorphins (the body’s natural pain relievers), can help reduce the perception of pain.

The Role in Human Development

From infancy through old age, affectionate touch plays a critical role in development and wellbeing. In early life, it is crucial for emotional and physical development; infants who receive regular, caring touch exhibit better emotional regulation, social skills, and stress responses. Throughout life, the presence of affectionate touch is associated with stronger social relationships and better emotional health.

Social and Cultural Variability

While the need for touch is universal, cultural norms and personal preferences greatly influence the expression and interpretation of affectionate touch. Different cultures have varying norms regarding who can touch whom, in what contexts, and in what manner. Understanding and respecting these differences is crucial in interpersonal interactions.

Challenges and Considerations

For some individuals, especially those with a history of trauma or sensory processing disorders, affectionate touch can be challenging or uncomfortable. In these cases, it’s important for communication and consent to guide interactions, allowing for boundaries to be respected and alternative methods of showing care and affection to be found.

Affectionate touch, with its myriad benefits and complexities, underscores the tactile nature of human connection and the profound impact of physical contact on emotional and physical health. Whether in the context of familial relationships, friendships, or romantic partnerships, affectionate touch remains a powerful means of conveying care, support, and love.

2. Comforting Touch:

Similar to affectionate touch, comforting touch aims to soothe and reassure. It can be particularly impactful in times of stress or sadness, offering solace and reducing anxiety.

Comforting touch is a type of physical contact specifically intended to provide reassurance, alleviate distress, and convey support and empathy to someone who may be experiencing emotional discomfort, anxiety, or sorrow. This form of touch can be particularly powerful in communicating nonverbally that one is not alone, offering a sense of safety and emotional support that words alone may not fully convey. Examples of comforting touch include hugs, holding hands, gentle strokes, back rubs, or simply placing a hand on someone’s shoulder.

Psychological and Physiological Effects

The act of comforting through touch can have profound psychological and physiological effects on both the giver and the receiver, due to the complex interplay of hormonal and neural responses involved:

Stress Reduction: Like affectionate touch, comforting touch can decrease cortisol levels, thereby reducing stress and inducing a calming effect. This can be particularly beneficial in moments of acute distress or during experiences of anxiety.

Release of Oxytocin: The physical act of comforting someone through touch can stimulate the release of oxytocin in the brain, enhancing feelings of trust, connection, and calmness. Oxytocin is also associated with reduced feelings of fear and anxiety.

Increase in Serotonin and Dopamine: Comforting touch can raise levels of serotonin and dopamine, neurotransmitters that are crucial for mood regulation and can contribute to feelings of wellbeing and happiness.

Enhancement of Immune System: By reducing stress and promoting relaxation, comforting touch may also have a positive impact on the immune system, contributing to overall health and wellbeing.

Role in Emotional Support and Bonding

Comforting touch plays a vital role in human connection and emotional support. It can strengthen bonds between individuals, providing a tangible manifestation of empathy and understanding. For those experiencing grief, anxiety, or distress, a comforting touch can be a powerful reminder of support and care, offering a sense of companionship in difficult times.

Cultural and Individual Differences

Cultural norms and personal boundaries significantly influence perceptions and expressions of comforting touch. What is considered an appropriate and comforting form of touch in one culture may not be the same in another. Similarly, individual differences, such as personal history, experiences with trauma, and personal comfort levels with physical touch, dictate how comforting touch is received and should be given. It’s important for individuals to communicate their boundaries and preferences regarding touch to ensure that attempts to provide comfort are welcomed and effective.

Challenges in Providing Comfort

Recognizing when and how to offer comforting touch requires empathy, sensitivity, and awareness of the recipient’s comfort level and preferences. Misjudged attempts at providing comfort through touch can sometimes lead to discomfort or misunderstanding. Therefore, it’s crucial to approach comforting touch with consideration and to seek verbal or nonverbal consent when possible.

Comforting touch is a potent tool in the human emotional toolkit, capable of bridging gaps in verbal communication and providing profound solace and support. Whether through a simple squeeze of the hand or a warm embrace, these gestures can significantly impact someone’s emotional state and sense of connection.

3. Playful Touch:

This encompasses light, teasing touches that are often part of playful interactions. Tickling is a common form of playful touch.

Playful touch refers to light-hearted, affectionate physical interactions that occur in the context of fun, play, or teasing. This type of touch is characterized by its informal and often spontaneous nature, serving to express joy, affection, and camaraderie among friends, romantic partners, family members, or even pets. Examples of playful touch include tickling, gentle nudging, playful wrestling, and other forms of nonaggressive physical interaction that evoke laughter, smiles, and a sense of closeness.

Psychological and Physiological Effects

Playful touch, much like other forms of positive physical contact, can have several beneficial effects on both mental and physical health:

Strengthening Bonds: Playful interactions foster a sense of connection and trust between individuals, strengthening social bonds and promoting feelings of belonging.

Reducing Stress: Engaging in playful activities and touch can trigger the release of endorphins, the body’s natural feel good chemicals, which can help reduce stress and promote feelings of happiness.

Enhancing Communication: Playful touch can be a form of nonverbal communication that conveys affection, interest, and camaraderie, enriching relationships by adding a dimension of light heartedness and fun.

Boosting Immune Function: The positive emotions elicited by playful interactions and touch can contribute to a healthier immune system by reducing the negative impact of stress on the body.

Role in Relationship Building

Playful touch plays a crucial role in the development and maintenance of relationships. It not only facilitates bonding but also introduces an element of fun and novelty, which can help keep relationships vibrant and resilient. In romantic relationships, playful touch can enhance emotional intimacy and serve as a precursor to more intimate forms of physical affection.

Cultural and Individual Differences

The interpretation and acceptance of playful touch can vary widely among different cultures and individuals. What is considered appropriate and enjoyable in one context may be perceived as intrusive or unwelcome in another. Cultural norms dictate the acceptability of various forms of touch, including who can engage in playful touch, in what settings, and to what extent.

Personal boundaries and individual experiences, such as one’s upbringing, personal history with touch, and current mood, also play significant roles in how playful touch is perceived and reciprocated. Consent and mutual enjoyment are key components of playful touch, making it essential for individuals to be attuned to each other’s signals and comfort levels.

Navigating Playful Touch

Given its nuanced nature, navigating playful touch requires sensitivity to context, relationship dynamics, and individual preferences. It’s important for individuals to communicate openly about their comfort with different types of touch and to respect each other’s boundaries. When done with consideration and mutual enjoyment, playful touch can be a delightful way to express affection, share joy, and strengthen connections.

4. Harmful Touch:

Actions that cause pain or discomfort, whether accidental or intentional, fall into this category. It’s important for social and personal boundaries to respect the difference between harmful touch and other, more positive forms of physical interaction.

Harmful touch encompasses any form of physical contact that inflicts physical pain, emotional distress, or discomfort on an individual, intentionally or unintentionally. This type of touch violates personal boundaries and can lead to a range of negative outcomes, including physical injury, psychological trauma, and lasting emotional harm. Harmful touch is not a means of positive communication but an infringement on personal autonomy and safety. It includes actions such as hitting, pushing, pinching, and any form of unwanted touch that can be classified as abuse or assault.

Psychological and Physiological Effects

The impact of harmful touch can be profound and long-lasting, affecting individuals on both psychological and physiological levels:

Psychological Trauma: Victims of harmful touch may experience a range of traumatic stress responses, including anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and feelings of shame or guilt. This can significantly impair their ability to form healthy relationships and trust others.

Physical Injury: Beyond immediate physical harm, harmful touch can lead to chronic health issues, such as pain syndromes or stress related illnesses, due to the body’s prolonged exposure to stress hormones.

Erosion of Trust: Experiencing harmful touch, especially from someone known and trusted, can profoundly erode one’s sense of safety and trust in others, impacting social interactions and relationships.

Impaired Social Development: Particularly in children, harmful touch can interfere with normal social development, leading to difficulties in forming healthy attachments and social relationships later in life.

Legal and Social Ramifications

Harmful touch not only has personal consequences but also legal and social implications. Laws in many jurisdictions protect individuals from unwanted or harmful physical contact, categorizing certain forms of harmful touch as criminal offenses, including assault and battery. Socially, recognition of the serious impact of harmful touch has led to increased awareness and efforts to prevent abuse and violence in homes, workplaces, and public spaces.

Prevention and Response

Preventing harmful touch involves education, awareness, and creating environments where respect for personal boundaries is a foundational principle. It’s crucial for individuals to understand consent and recognize the importance of respecting others’ physical autonomy. In instances of harmful touch, support systems, including counseling, legal recourse, and community resources, plays a vital role in recovery and ensuring the safety of affected individuals.

Responding to harmful touch appropriately involves recognizing the signs of abuse or assault, providing support to survivors, and taking action to prevent further harm, whether through intervention or by providing resources for help and recovery. Encouraging open discussions about consent, personal boundaries, and the impact of harmful touch is essential in fostering safer communities and relationships.

In conclusion, harmful touch is a serious violation that can have lasting effects on an individual’s wellbeing and health. Recognizing, preventing, and appropriately responding to harmful touch is crucial in promoting respect, safety, and health within societies.

5. Professional Touch:

This type of touch is context dependent and includes interactions such as a handshake, a pat on the back in a professional setting, or the physical examinations conducted by healthcare providers.

Professional touch refers to physical contact that occurs in a clinical or therapeutic context, provided by healthcare professionals, such as doctors, nurses, physical therapists, and massage therapists, among others. This type of touch is purposeful, consent based, and aimed at achieving specific health, wellness, or therapeutic goals. Professional touch encompasses a wide range of interactions, from medical examinations and procedures to therapeutic massages and physical therapy interventions.

Characteristics of Professional Touch

Goal Oriented: Professional touch is applied with specific objectives in mind, such as diagnosing a condition, promoting healing, or providing relief from pain.

Boundaries and Consent: It is governed by strict professional boundaries and ethical guidelines to ensure the patients or client’s comfort, dignity, and autonomy. Informed consent is a cornerstone of professional touch, ensuring that the individual understands and agrees to the nature and purpose of the physical contact.

Training and Competence: Professionals who provide touch as part of their practice are trained and certified to perform their specific roles, ensuring that touch is applied safely, effectively, and appropriately to the individual’s needs.

Psychological and Physiological Effects

Professional touch can have significant positive impacts on both psychological and physiological wellbeing:

Pain Relief and Physical Healing: Techniques such as massage therapy, physical therapy, and certain medical procedures can directly contribute to pain relief, improved mobility, and physical healing.

Stress Reduction: Many people experience reduced stress and increased relaxation as a result of professional touch, partly due to the release of endorphins and the physical comfort provided by therapeutic touch.

Emotional Support: Even in a professional context, the act of being touched can convey empathy, care, and support, contributing to a sense of being cared for and understood.

Ethical Considerations

Given the intimate nature of touch, professionals must navigate ethical considerations with sensitivity and respect for individual boundaries. This includes:

Maintaining Professionalism: Keeping interactions professional and focused on the client or patient’s needs and wellbeing.

Privacy and Dignity: Ensuring that procedures involving touch are conducted in a manner that preserves the individual’s privacy and dignity.

Cultural Sensitivity: Being aware of and respecting cultural differences in perceptions and acceptability of touch.

Importance in Healthcare and Therapeutic Settings

Professional touch is an indispensable tool in many healthcare and therapeutic disciplines. It not only aids in the diagnosis and treatment of physical conditions but also plays a crucial role in providing comfort, conveying compassion, and building a therapeutic rapport with clients or patients. The effectiveness of professional touch, coupled with respect for ethical standards and individual boundaries, underscores its value in supporting overall health and wellbeing.

6. Social Touch:

This refers to touches that occur in social interactions, which can vary widely in meaning and appropriateness based on cultural norms and personal boundaries. It can range from handshakes and patting on the back to more intimate forms of touch among close friends or acquaintances.

Social touch refers to the physical contact that occurs in the context of interpersonal interactions, conveying a range of emotions and intentions, such as affection, support, greeting, or bonding. It is an essential aspect of human connection and communication, deeply rooted in our social behaviors and cultural practices. This type of touch can include handshakes, hugs, pats on the back, touches on the arm, and other gentle forms of contact. Social touch plays a significant role in building and maintaining relationships, expressing empathy, and enhancing social bonding.

Psychological and Physiological Effects

The impact of social touch extends beyond mere physical contact, influencing both psychological wellbeing and physical health:

Enhanced Bonding and Social Cohesion: Social touch increases levels of oxytocin, sometimes referred to as the “bonding hormone,” which fosters feelings of trust, strengthens social connections, and enhances group cohesion.

Emotional Communication: Touch is a powerful nonverbal communication tool that can convey a wide range of emotions more effectively than words alone, from empathy and love to gratitude and consolation.

Stress Reduction and Wellbeing: Social touch can trigger the release of endorphins and reduce cortisol levels, alleviating stress, promoting relaxation, and contributing to overall wellbeing.

Improved Immune Function: Some studies suggest that positive social interactions and touch can boost the immune system, making individuals less susceptible to illnesses.

Cultural Variability

The norms and expectations surrounding social touch vary widely across cultures, affecting how touch is perceived and what forms of touch are considered appropriate or inappropriate. Some cultures are more tactile, using touch frequently as a form of communication, while others may reserve touch for very close relationships or specific contexts. Understanding these cultural nuances is crucial for navigating social interactions successfully and respectfully.

Individual Differences

Preferences and comfort levels with social touch also vary widely among individuals, influenced by personal history, personality, and past experiences. Some people naturally seek out and initiate physical contact, while others may find excessive touch overwhelming or uncomfortable. Respect for personal boundaries and consent is paramount in all social touch interactions to ensure that touch serves its intended purpose of fostering positive connections.

Role in Human Development and Relationships

Social touch is not only beneficial but also essential for human development and emotional wellbeing. From infancy, touch plays a critical role in parent child bonding, healthy development, and emotional regulation. Throughout life, social touch remains a key element in expressing affection, building trust, and maintaining the emotional and psychological health of relationships.

Challenges and Considerations

In today’s globalized and digitally connected world, navigating social touch requires sensitivity to individual and cultural differences, as well as an awareness of the context in which touch occurs. The increasing awareness of consent and personal boundaries has also highlighted the importance of ensuring that social touch is always welcome and respectful.

In conclusion, social touch is a fundamental human need and a powerful form of communication that, when used thoughtfully and appropriately, can significantly enhance interpersonal relationships and individual wellbeing.

Understanding the different types of touch and their impacts on human emotion and physiology underscores the complexity and significance of this sense in our daily lives and interpersonal relationships.